Lecture 13 Services

This lecture discusses a component of Android development that is not immediately visible to users: Services41.

Services are sort of like Activities that don’t have a user interface or user interaction directly tied to them. Services can be launched by Activities or Applications, but then do their own thing in the background even after the starting component is closed (this is distinct from ASyncTask, which had its lifecycle tied to that of its containing Activity). Once a Service is started, it keeps running until it is explicitly stopped (Services can be destroyed by the OS to save memory, similar to an Activity, but Services have higher “priority” and so aren’t killed as readily).

Some common uses for a Service include:

- Downloading or uploading data from/to a network in the background even if the app is closed

- Saving data to a database without crashing if the user leaves the app

- Running some other kind of long-running, “background” task even after the app is closed, such as playing music!

An important thing to note about Services: a Service is not a separate process; it runs in the same process as the app that starts it (unless otherwise specified). Similarly, a Service is not a Thread, and in fact doesn’t need to run outside the UI thread! However, we quite often do want to run the service outside of the UI Thread, and so often have it spawn and run a new Runnable Thread. When we say a Service runs “in the background”, we mean from a user’s perspective rather than necessarily on a background thread.

This lecture references code found at https://github.com/info448-s17/lecture13-services.

13.1 IntentServices

To create a Service, we’re going to subclass Service and override some lifecycle callbacks, just like we’ve done with Activity, Fragment, BroadcastReceiver, and most other Android components. In this sense, Services are in fact implemented like Activities that run without a user interface (“in the background”).

Because Services will be performing extra background computation, it’s important to also create a separate background thread so that we don’t block the Main Thread. Since making a Service that does some (specific) task in a background thread is so common, Android includes a Service subclass we can use to do exactly this work. This class is called IntentService—a service that responds to Intents and does some work in response to them.

- An IntentService does similar work to

ASyncTask, but with the advantage that it will keep doing that work even if the Activity is destroyed! IntentServicewill listen to any incoming “requests” (Intents) and “queue” them up, handling each one at a time. Once the service is out of tasks to do, the service will shut itself down to save memory (though it will restart if moreIntentsare sent to it). Basically, it handles a lot of the setup and cleanup involved in Service on its own!(This lecture will start with

IntentServicebecause it’s simpler, and then move into the more generic, complex version of Services).

We create an IntentService by defining a new class (e.g., CountingService) that subclasses Intent Service.

- Implement a default constructor that can call

super(String nameForDebugging). This allows the class to be instantiated (by the Android framework; again, like an Activity). Also implement the

onHandleIntent(Intent)method. IncomingIntentswill wait their turn in line, and then each is delivered to this method in turn. Note that all this work (delivery and execution) will happen in a background thread supplied byIntentService.For example, we can have the Service (when started) log out a count, pausing for a few seconds between. This will represent “expensive” logic to perform, a la accessing a network or a database.

for(int count=0; count<=10; count++){ Log.v(TAG, "Count: "+count); try { Thread.sleep(5000); //sleep for 5 seconds } catch (InterruptedException e) { Thread.currentThread().interrupt(); } }

Just like with Activities, we also need to declare the <service> in the Manifest, as a child of the <application>:

<service android:name=".CountingService" />Finally, we can send an Intent to the Service by using the startService() method. This is similar to startActivity(), but is for services! We can use explicit intents just like with Activities, and could even include Extras if we wanted to label and track the specific Intents sent to the service.

- When the Service starts, we can see it start counting (but without blocking the UI Thread). We can also destroy the Activity and see that the Service keeps running.

If we want to have the Service to interact with the user interface, such as displaying a Toast, we will need to make sure that occurs on the UI Thread (you cannot change the UI on a separate thread). This requires inter-thread communication: we need to get a message (a function call) from the background thread to the UI Thread. We can perform this communication using a Handler, which is an object used to pass messages between Threads—it “handles” the messages!

We instantiate a

new Handler()object (e.g., in the Service’sonCreate()callback), calling a method on that object when we want to “send” a message. The easiest way to send a message is to use thepost()function, which takes aRunnable()method which will be executed on the Main Thread:mHandler.post(new Runnable() { @Override public void run() { Toast.makeText(CountingService.this, "Count: " + count, Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); } });

13.1.1 The Service Lifecycle

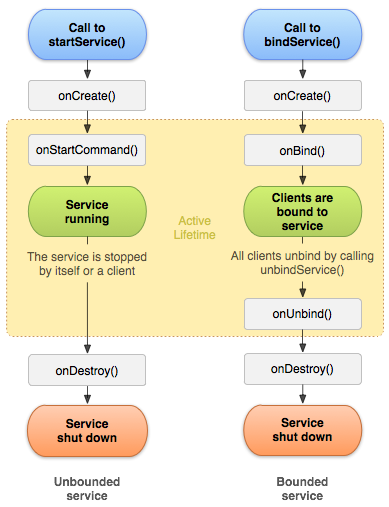

Having demonstrated the basic usage of a service, consider what is going on “under the hood”—starting with the Service lifecycle. There are actually two different “types” of Services, with different variations of the lifecycle. Started Services (or “unbound” Services) are those that are initiated via the startService() function, as in the above example. The other option, Bound Services, are Services that have “client” Activities bound to them to interact with; see below for details.

Service lifecycle diagram, from Google42

Just like with Activities, Services have an

onCreate()method that is called when the Service is first created. Since Services don’t have a user interface to set up, so we don’t often do a lot in here.- IntentService already overrides this in order to set up a “message queue” so that it can queue up Intents (tasks) to run one at a time.

The most important callback for a Started Service is called

onStartCommand(). This method is called when the Service is sent a command by another component (via an Intent). Importantly,onStartCommand()is not only called when the Service is started for the first time, but whenever the Service receives an Intent to start (even if the Service was already running)! These Intents are those sent viastartService().- Note that when working with an IntentService specifically,

onStartCommand()will “queue” any incoming Intents. When it is the specific Intent’s turn to be “run”, that Intent is automatically passed to theonHandleIntent()method, which executes on a background thread (similar toAsyncTask#doInBackground()). This callback is not part of the normal Service lifecycle, but is a special helper method used by IntentService—similar to howonCreateDialog()is a special method used byDialogFragments.

- Note that when working with an IntentService specifically,

The

onBind()andonUnbind()callbacks are used for bound services, and are discussed below.- IntentService does have a default

onBind()implementation that returnsnull.

- IntentService does have a default

Finally, Services have an

onDestroy()callback, which is again equivalent to the Activity callback.- In general, Services have to be manually told to stop. We stop a Service by using

stopService(Intent)to send that Service a “stop” Intent. The Service can also stop itself by callingstopSelf(). - Important: When told to stop, an IntentService will finish up handling any Intents that are currently “running”, but any other Intents that are “queued” will be removed. Once there are no more queued Intents, an IntentService will call

stopSelf(), thereby causing theonDestroy()callback to be executed.

- In general, Services have to be manually told to stop. We stop a Service by using

Practice: fill in the callback functions with Log or Toast messages to see how and when they are executed. For example:

public int onStartCommand(Intent intent, int flags, int startId) {

Toast.makeText(this, "Intent received", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

return super.onStartCommand(intent,flags,startId);

}As a last point to note about the Service lifecycle consider the int that is returned by onStartCommand(). This int is a flag that indicates how the Service should behave43 when it is “restarted” after having been destroyed:

START_NOT_STICKYindicates that if the Service is destroyed by the system, it should not be recreated. This is the “safest option” to avoid extraneous service executions; instead, just have the application restart the Service.START_STICKYindicates that if the Service is destroyed by the system, it should be recreated when possible. At that point,onStartCommand()will be called with delivered anullIntent (unless there were other start Intents waiting to be delivered, in which case those are used). This option works well for media players or similar services that are running indefinitely (rather than executing specific commands).START_REDELIVER_INTENTindicates that if the Service is destroyed by the system, it should be recreated when possible. At that point,onStartCommand()will be called with the last Intent that was delivered to the Service (and any other Intents are delivered in turn). This option is good for Services that actively perform jobs that need to be resumed, such as downloading a file.

In other words: services may get killed, but we can specify how they get resurrected! And of course, we can and should return different values for different starting commands (Intents): so the Intent to download a music file might return START_REDELIVER_INTENT, but the Intent to play the music file might return START_STICKY.

13.2 Example: A Music Service

One of the classic uses for a background service is to play music, so we will use that as an example. It is possible to play music directly from an Activity, and the music will even keep playing as long as the Activity is alive. But remember that Activities are fragile, and can be destroyed at any moment (whether by us or by the system to save resources). So in order to keep our music playing even as we go about other tasks, we should use a Service. Services have higher “priority” in the eyes of the Android system, and so don’t get sacrificed for resources as readily as normal Activities.

13.2.1 MediaPlayer

In order to make a music service, we need to briefly explain how to play music with MediaPlayer. This is the main API for playing sound and video (e.g., if you want to play .mp3 files).

Android actually has a toal of three (3) audio APIs! The SoundPool API is great for short sound effects that play simultaneously (though you need to do extra work to load those clips ahead of time), as with simple games. The AudioTrack API allows you to play audio at a very low level (e.g., by “pushing” bytes to a stream). This is useful for generated Audio (like MIDI music) or if you’re trying to do some other kind of low-level stuff.

MediaPlayer is very simple to use, particularly when playing a locally defined resource (e.g., something in res/raw/). You simply use a factory to make a new MediaPlayer object, and then call .play() on it:

MediaPlayer mediaPlayer = MediaPlayer.create(context, R.raw.my_sound_file);

mediaPlayer.start(); // no need to call prepare(); create() does that for youWe can also call .pause() to pause the music, .seekTo() to jump to a particular millisecond, and .stop() to stop the music.

- Note that when we

stop(), we also need to release any resources used by theMediaPlayer(to free up memory):

mediaPlayer.release();

mediaPlayer = null;We can also implement and register a MediaPlayer.OnCompletionListener to handle when a song finishes playing.

Finally, it is possible to use MediaPlayer to play files from a ContentProvider or even off the Internet!

String url = "http://........"; // your URL here

MediaPlayer mediaPlayer = new MediaPlayer();

mediaPlayer.setAudioStreamType(AudioManager.STREAM_MUSIC);

mediaPlayer.setDataSource(url);

mediaPlayer.prepareAsync(); //prepare media in the background (buffering, etc)

//.prepare() for synchronous buffering

mediaPlayer.setOnPreparedListener(this); //handle when file is buffered

mediaPlayer.start();13.2.2 Creating a Service

In order to make our music service, we are going to subclass the Service class itself (don’t forget to include the Service in the Manifest) and manually set up all the pieces. Specifically, we will fill in the lifecycle callbacks:

onCreate()we can include, though it doesn’t need to do anything.onStartCommand()should create and start our MediaPlayer. We can returnSTART_NOT_STICKYso the music doesn’t start up again randomly if the system needs to destroy the Service (since it won’t get recreated).Important: Normally with a Service we would create a background thread to handle any extraneous work (such as preparing the music to play, as done with the

create()method). However, this may not be necessary for MediaPlayer when loading resources.onDestroy()can stop, release, and clean-up the MediaPlayer. We can implement this in a separate helper function for reuse.- If we want to handle pausing, we can specify that in the Intent we send to the service (e.g., via a custom ACTION or an Extra). But a more effective approach is to use Service Binding; see below for details.

We can now have our Activity startService() and stopService() in order to play our music in the “background”, even if we leave and return to the Activity!

13.3 Foreground Services

Services are normally “background” tasks, that run without any user interface and that the user isn’t aware of (e.g., for downloading or uploading data, etc). But music playing is definitely something that the user is aware of, and in fact may want to interact with it! So we’d like the Service to have some kind of user interface, but we’d like to still keep that Service separated from an Activity (so that it can run with the Activity being active).

To do this, we use what is called a Foreground Service. Foreground Services represent Services that are divorced from Activities (they are Services after all), but the user is aware of them—and accordingly, have an even higher survival priority if the OS gets low on memory!

Foreground services require a Notification in the status bar, similar to the Notifications we’ve created before. This Notification will effectively act as the “user interface” for the Service, and let the user see and be aware of its execution!

We create this Notification inside the Service’s onStartCommand() method, then pass it to the startForeground() method in order to put our Service in the foreground:

String songName = "The Entertainer";

PendingIntent pendingIntent = PendingIntent.getActivity(getApplicationContext(), 0,

new Intent(getApplicationContext(), MainActivity.class), PendingIntent.FLAG_UPDATE_CURRENT);

Notification notification = new NotificationCompat.Builder(this)

.setSmallIcon(android.R.drawable.ic_media_play)

.setContentTitle("Music Player")

.setContentText("Now playing: "+songName)

.setContentIntent(pendingIntent)

.setOngoing(true) //cannot be dismissed by the user

.build();

startForeground(NOTIFICATION_ID, notification); //make this a foreground service!Some details about this Notification:

- We build and set the icon, title, and text as in the previous lecture.

- We give the Notification a

PendingIntentto run when selected. This PendingIntent can just open up ourMainActivity, allowing us to control the Player. (Alternatively, we could use Notification Actions to control the music directly). - We set the Notification to be ongoing, in order to enforce that it cannot be dismissed by the user.

Importantly, once we are done doing foreground work (e.g., playing music), we should call stopForeground(true) to get rid of the foreground service. This is a good thing to do in our stopMusic() helper (called from onDestroy()).

There are a couple of other details that you should handle if you’re making a full-blown music player app, including: keeping the phone from going to sleep, playing other audio at the same time (e.g., notification sounds; ringtones), switching to external speakers, etc. See the guide for more details.

13.4 Bound Services

As mentioned above, there are two “types” of Services: Started Services (Services launched with startService()) and Bound Services. A Bound Service is a Service that acts as the “server” in a client-server setup: it allows for client Activities to “connect” to it (bind it) and then exchange messages with—primarily by calling methods on the Service. These messages can even be across processes, allowing for interprocess communication! This is useful when you want interact with the Service from an Activity in some way (e.g., if we want to pause() our music), or if we want to make the service’s capabilities available to other applications.

We make a Bound Service by having the Service implement and utilize the onBind() callback. This method returns an IBinder object (the I indicates that it’s an Interface, following a Java convention common in enterprise software). When Activities connect to this Service (using the bindService() method), this IBinder object is passed to them, and they can use it to get access to the Service process to call methods on it. Effectively, the binding process produces an object that represents that Service, so Activities can call methods on the Service without needing to send it Intents!

As an example, let’s add the ability to “pause” the music being played as a bound service:

The first thing we need to do is have our Service implement the onBind() method. To do this, we will need an IBinder object to return (that is: an object of a class that implements the IBinder interface). For “local services” (e.g., Services that are run in the same process), the easiest way to get an IBinder is to extend the Binder class:

private final IBinder mBinder = new LocalBinder(); //singleton instance variable

public class LocalBinder extends Binder { //implements IBinder

//binder class methods will go here!

}- Our local version starts “empty” for now; we’ll add details below.

- We will just return this object from

onBind().

Because the Activity is given a copy of this LocalBinder object, that class can be designed to support the Activity communicating with the Service in a couple of different ways:

The

IBindercan providepublicmethods for the Activity to call. These methods can then access instance variables of the Service (since theLocalBinderis a nested class). This causes theIBinderto literally act as the “public interface” for the Service!//in LocalBinder public String getSongName() { return songName; //access Service instance variable }The

IBindercan provide access to the Service itself (via a getter that returns theServiceobject). The Activity can then call any public methods provided by thatServiceclass.//in LocalBinder public MusicService getService() { // Return this instance of this Service so clients can call public methods on it! return MusicService.this; }The

IBindercan provide access to some other object “owned” by the Service, which the Activity can then call methods on (e.g., theMediaPlayer). This is somewhat like a compromise between the first two options: you don’t need to implement a specific public interface on theIBinder, but you also don’t have to provide full access to your Service object! This is good for only exposing part of the Service.

In the Activity, we need to do a bit more work in order to interact with the bound Service. We bind to a Service using bindService(Intent, ServiceConnection, flag). We can do this whenever we want the Service to be available (onStart() is a good option, so it is available when the Activity is active).

- The Intent parameter should be addressed to the Service we want to bind.

The

ServiceConnectionparameter is a reference to an object that implements theServiceConnectioninterface, providing callbacks that can be executed whe the Activity connects to the Service. We can have the Activity implement the interface, or create a separate anonymous class:/** Defines callbacks for service binding, passed to bindService() */ private ServiceConnection mConnection = new ServiceConnection() { public void onServiceConnected(ComponentName className, IBinder service) { // We've bound to LocalService, cast the IBinder and get LocalService instance LocalBinder binder = (LocalBinder) service; mService = binder.getService(); mBound = true; } public void onServiceDisconnected(ComponentName arg0) { mBound = false; } };The

onServiceConnected()callback handles the actual connection, and is where we get access to thatIBinder. We can use thatIBinderto fetch the Service object to call methods on, saving that as an instance variable to do stuff to it! We’ll also track whether or not the Service has been bound to avoid anynullerrors.Finally, the

flagparameter indicates some options for how the Service should be bound (e.g., for specifying survival priority).Conetxt.BIND_AUTO_CREATEis a good default, specifying that the binding should create the Service object if needed.

Once a Service is bound, we can call methods on that Service (which must exist!)—allowing us to support the “pause” button.

We should also call unbindService() when the Activity stops, in order to free up resources:

protected void onStop() {

if (mBound) {

unbindService(this);

}

super.onStop();

}

Keep in mind that binding a Service DOES NOT call onStartCommand(), but simply creates the Service and gives us access to it! Bound Services are not by defaul considered “started”, and are generally kept around by the OS as long as they are bound. If we do “start” a Bound Service (e.g., with startService()), we will need to remember to stop it later!

This example is just for local services (that are accessed within the same process—within the same Application). If we want the Service to be available to other processes (i.e., other Applications), we need to do more work. Specifically, we use Handler and Messenger objects to pass messages between these processes (similar to the example we did for passing messages between threads); for more details, see the example in the guide, as well as the complete sample classes MessengerService and MessengerServiceActivities.